Content warning: L'age d'or deals with some fairly adult content and shocking themes, which will seem even more shocking when taken out of context!

A very brief introduction to Sigmund Freud

Freud's ideas are often casually dismissed by those who have probably never even studied his work. Granted, a lot of his work considers complex sexual desires and transgressive ideas. Yet these ideas shaped the ideology of the 20th century and still provide a fascinating framework by which to understand ourselves today.

In brief, Freud believed that we have deep desires within us that we must suppress on a daily basis. These desires are called drives. You may have heard the phrase 'sex drive'; it's a commonly used expression and it's a Freudian term for a desire to have sex. Another Freudian drive is the death drive. This is the desire to destroy ourselves and to ruin everything.

At the heart of our self is the ego. This is our pure self, if you like. But the ego is in conflict with the id, a force that represents our innermost desires. your id wants you to do whatever feels best, without thinking about the consequences (Freud refers to this concept as the pleasure principle). However, we cannot simply get drunk all the time and running down the street punching people (assuming this is what we want to do). So another force, our superego acts as a foil to the id, and keeps the ego in balance. Sometimes the id wins, and we may do something stupid we regret. And some people are more prone to letting their id or their superego win over than other people.

So far, this is about as complex as a a cartoon with an angel and devil having an argument on the character's shoulder

Freudian symbolism in the music video to Satisfaction by Benni Bennassi

The music video is clearly heavily symbolic of sex. The provocative dress of the female performers is connotative of sex. However, this is reinforced through mid shots of the women’s bodies covered in sweat, which is connotative of the sexual act. We also have continual close ups of a drill bit entering masonry, which is clearly symbolic of heterosexual sexual intercourse, constructing a heteronormative worldview. Finally, ECUs of mouths, lips and teeth connote sex and and a fierce, aggressive and even powerful attitude.

Examples of the id overpowering the superego in L’age d’or

- Knocking the blind man over

- Slaps his girlfriend’s mother

- Kicks a dog

- Stamps on a beetle

- Kid being shot

- Public sex

- Throwing stuff out of the window

- Rips up pillow

- Sucking the toe of the statue

- Running off with the conductor

ID and superego conflict in the ‘post arrest’ scene in L'age d’or

- The Man shows his captors a contract of sorts (actually a set of blueprints), with a seal on the bottom. By showing this strange contract, the Man is able to use dream logic to escape imprisonment

- The Man is suddenly transformed into a glamorous spy, with the power of the government behind him

- Instead of treating his captors with respect, he begins to sing like a child to explain his ludicrous story that he is actually a spy

- Perhaps this joke is a criticism of power and corruption. Rich and powerful people, for example politicians are able to get away with crimes that common people cannot. This silly joke draws attention to a huge issue that exists in society

In what ways are themes of sexual fetishism encoded in the garden/toe sucking scene?

Mise-en-scene

- The MES of the rich, dark lipstick has connotations of seduction and beauty. However, the unpleasant nature of the scene constructs a binary opposition between beauty and unpleasant sexuality. Once more, this positions the spectator in an uncomfortable mode of address

- The MES of the woman’s suddenly old face symbolises the loss of youth and the inevitability of aging. It suggests that even in our dreams, we cannot completely reject the death drive

- The woman sucks the toe of a female statue, connoting a homoerotic experience, which furthers the controversial potential of this sequence

- The rich and fancy costumes construct a binary opposition with the messiness of the act. The man dumps the woman on the dirty floor. By dirtying her dress, the man is stripping away the elements of society and pursuing his deepest desires

Cinematography

- Close ups of toe sucking present a highly controversial and unpleasant spectatorial response, which is emphasised by the repetitive editing

- A POV shot from the man’s perspective suddenly and confusingly shows the woman as an old woman. Suddenly seeing the passionless future ahead of him, the man suddenly looses all sexual interest, and instead simply lies down with.

- High angle shot of the man holding the legs of the woman implies he is about to have oral sex with her, a passionate and erotic act. However, he changes his mind, pushes her legs together again, and then withdraws

Performance

- The man seems extremely angry when he is interrupted, and moves in an exaggerated way. His sexual frustration is clear, and this is one of many times he has been sexually frustrated.

- Both performers become visibly tired and upset when commencing sex. Now the sex is not forbidden or being withheld, it has lost all attraction

Der Lieberstod

"Liebestod" ([ˈliːbəsˌtoːt] German for "love death") is the title of the final, dramatic music from the 1859 opera Tristan und Isolde by Richard Wagner. It is the climactic end of the opera, as Isolde sings over Tristan's dead body.

The music is often used in film and television productions of doomed lovers.[1]

(straight from Wikipedia, lolol)

Softly and gently

how he smiles,

how his eyes

fondly open

—do you see, friends?

do you not see?

how he shines

ever brighter.

Star-haloed

rising higher

Do you not see?

- The conclusion to this opera very explicitly states that true love can only be attained through death and tragedy, and that in doing so, the star crossed lovers have become more beautiful than ever.

- Moreover, the Liebestod keeps building to a climax, before interrupting itself, and never being resolved. It is both beautiful and frustrating at the same time

How does the death of the maid/killing the child sequence construct an alienating and upsetting mode of address?

- While this sequence features a range of powerful classical music as it’s soundtrack, the actual moment of the murder is notable through the lack of non-diegetic music. This sudden shift to naturalistic film making techniques is further anchored through the simplistic use of montage to construct an unnerving and fearful mode of address

- However, the sequence is clearly absurd. This absurdity is constructed through the binary opposition between the performance of knocking the cigarette out of the hands of the groundskeeper, and the cold, execution style murder of the child. This lack of emotion is emphasised through the CU of the head of the dead child being shot again. This highly transgressive aesthetic positions us as the murderer, and emphasises feelings of discomfort, and the commentary on societal values. This is a common technique used in transgressive media, where exaggeration emphasises a point.

- The groundskeeper is clearly working class, through his situation in the setting. We cut from the lavish party to the groundskeeper sitting outside the party. His working class clothes form a binary opposition with the extravagantly dressed bourgeoisie. This action could be symbolic of anger and rebellion, although killing a child is hardly an effective rebellion

- We cut to the balcony where the rich partygoers seem to show interest and awareness of the death of the child. However, rather than try to help, we are presented with a tracking shot of the gossiping faces of the bourgeoisie. The use of editing confirms the lack of concern: the partygoers emerge back into the party, still gossiping. This confirms one of the primary ideologies of the film: the hatred of the working class by the rich and powerful

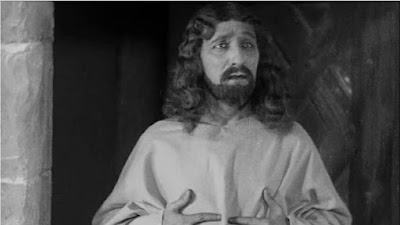

How is spectatorial discomfort constructed and intensified through film language in the ‘120 Days of Sodom’ scene of L’age d’or?

- The casting and performance of Jesus is both uncanny and his performance connotes discomfort through his own discomfort

- The repetitive, stomping march of the drums constructs a sense of tension and apprehension. The drums are nightmarish and panic inducing

- The sense of desperation and misery is further anchored through the static and unchanging cinematography. The MES of the door slowly being opened constructs a sense of horror and apprehension

- Long shot duration, with a lack of editing

- The final shot of the scalps of the young girls nailed to the cross is both transgressive and blasphemous

- The cheery fanfare played over the scene of sadism and torture and murder is contrapuntal, and emphasises the horror

- The drumming becomes more quiet to emphasise the pleonastic sound of the girl screaming

- Jesus loses his beard after killing the girl, and looses his identity in the process. Weeping as he walking through the snowing path, this is a particularly horrible image

- The intertitles describe horrific events that the audience are forced to read